Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex

The tenacious brain: How the anterior mid-cingulate contributes to achieving goals.

The Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex (The AMCC) has been subject to extensive scientific research and I will be referencing “The Tenacious Brain: How the Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex Contributes to achieving goals” and possibly other articles in the research of this area of the brain will be included as well. For the rest of this article I will be referencing to the Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex as the AMCC.

Tenacity: The abililty to move through discomfort

When faced with a difficult challenge, such as mastering complex equations or training for a marathon, many individuals will find the effort too costly, and withdraw. Others, however, will marshal their resources, and persist in their efforts against the same challenges, even in the absence of immediate reward. This individual difference has received a great deal of attention in recent years, as growing research indicates that individuals who persevere in the face of challenging situations show better life outcomes in the domains of health, academic achievement, and career success (Duckworth and Quinn, 2009; Duckworth and Gross, 2014).

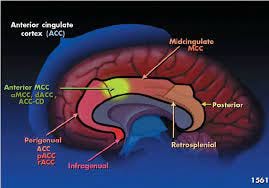

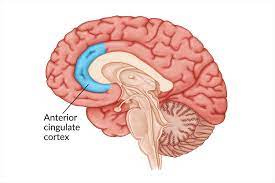

LOCATION:

The AMCC, located in the anterior portion (The Front) of the brain and is oriented in such a manner that it’s connection, to other parts of the brain, the AMCC integrates information from multiple brain networks to support its drive toward goal oriented behaviors. In other words The AMCC doers not operate autonomously, but in conjunction with… The anterior mid cingulate cortex (AMCC) is a region of the brain that is part of the frontal cortex. It is located at the back of the frontal lobe and is involved in decision making, attention, and working memory.

FUNCTION:

“aMCC might provide the motivational drive to perform actions, playing an excitatory and/or inhibitory role on these motor circuits”

aMCC includes also dopaminergic, noradrenergic and serotonergic terminals

The AMCC serves to grow based on overcoming challenging events toward a particular goal. Note the words, tenacity, perseverance, resilience, and drive. Activation of the “Tenacious Brain” the AMCC region is indicates that throughout difficult tasks most notably through frustrating events along with the desire to avoid said events resulted in a positive correlate in stimulation.

ACTIONABLE STEPS:

Embrace the difficulties of the day. Ranging from an earlier wake up time with less than optimal sleep, in order to get to an event that you’ve promised yourself in attending,

to jumping into that cold bath ranging from 37-50 degrees Fahrenheit, or simply working through some basic arithmetic and constantly get stumped on solving the problem with the correct sequence in the formula.

The AMCC sees no difference in any of these tasks, all of which require reasonable strain in overcoming frustration toward reaching the end. This part of the brain will showcase growth when you embrace doing these tasks, and rest assured you do not have to enjoy them, actually not enjoying said tasks will actually aid in more growth of the AMCC in opposition to embracing the tasks whole heartedly and enjoying them. So at the end of the road of any circumstance that has been challenging for you, no matter the gain and no matter the loss, you can find comfort in the fact that your discomfort most certainly amounted in at least growing your Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex.

Research:

Clinical research in humans has also indicated that damage to the aMCC or its connections can produce profound motivational changes. Reports of damage to the cingulate influencing motivation go back to Papez (1937, see (Szczepanski and Knight, 2014)], who observed that tumors pressing on the cingulate cortex led to “indifference to the environment, change in personality or character, [and a] stuporous or comatose state”. More recent studies have connected damage to the aMCC region with motivational impairment, apathy and inability to plan for long term goals (Devinsky et al., 1995; van Reekum et al., 2005; Szczepanski and Knight, 2014; Ducharme et al., 2017).

Stimulation:

Patients generally described the experience of aMCC stimulation as evoking the feeling of preparing for a difficult challenge. As one patient put it: “I started getting this feeling like … I was driving into a storm. […] like, you’re headed towards a storm […] and you’ve got to get across the hill and all of a sudden you’re sitting there going how am I going to get over that, through that?”

Depression:

Dysfunction of the aMCC seems particularly relevant to motivational problems, rather than hedonic components of depression. It has been shown that the degree of reduction in aMCC volume predicts severity of apathetic symptoms in depression (Lavretsky et al., 2007).

Aging:

Emerging research suggests that exceptional cases of healthy aging may be associated with increased tenacity. While in the majority of elderly people, episodic memory function declines with age (Grady and Craik, 2000; Cansino, 2009) accompanied by a number of age-related neurobiological changes, including structural atrophy (Brickman et al., 2007; Bakkour et al., 2013), loss of intrinsic network coherence (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010), and altered brain activity during memory (Grady et al., 2006; Maillet and Rajah, 2014), there are exceptions. Multiple recent studies have identified a remarkable subgroup of elderly people, known as ‘superagers’, whose performance on some cognitive measures is equivalent to middle aged (Gefen et al., 2014) and even young (Sun et al., 2016) adults, despite their advanced age.

Citation:

Touroutoglou, A., Andreano, J., Dickerson, B. C., & Barrett, L. F. (2020). The tenacious brain: How the anterior mid-cingulate contributes to achieving goals. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior, 123, 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2019.09.011